Conversations with Angels

programme note by Kate Brown for the SEMC production

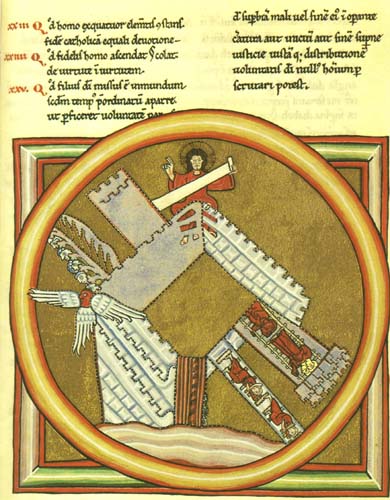

Hildegard, her scribe Volmar and one of her nuns.

from the Codex Latinus 1942

| Hildegard’s early life Hildegard was born in 1098, the tenth child of Hildebert and Mechthild von Bermersheim, minor nobility of the Holy Roman Empire. She must have been an unusual child even in her infancy, for she was dedicated to the church at the age of eight, not just as a noble pupil, staying until she might be married, but for her lifetime - her earliest biographer speaks of the dedication in terms of a tithe, given to the church irrevocably. She went to live with Jutta von Spanheim, an anchoress - a female hermit - enclosed in a small cell attached to the abbey of Disibodenberg. The hill of St Disibod rises at the confluence of the Glan and Nahe rivers, some way south of Bingen. In the eighth century, the Celtic monk Disibod and his companions settled here, bringing Christianity to the region. The area fell under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Mainz, and in the tenth century a foundation of twelve canons was established, to which a small enclosure for women was attached. A religious life for a medieval woman was not necessarily a total retreat from public life, even if the enclosure was a strict one. Jutta herself was of a noble family, but did not care for marriage, preferring a certain independence at the cost of worldly comfort. Some types of religious women gave up much less. The canonesses of Gandersheim kept significant freedoms - their own money, servants and books, entertainments and travel, and they could leave to get married when a suitable offer presented itself. It was a way for a clever woman to have a place of her own in the world, and the eleventh and twelfth centuries saw many powerful abbesses, well-connected to both temporal and ecclesiastical authority. The canons languished on the Disibodenberg, though the women retained their presence. About the time of Hildegard’s birth, at the turn of the eleventh century, an energetic Archbishop (so energetic he found himself frequently at odds with the secular powers of the Empire) founded a new abbey with Benedictine monks from Mainz. There was a long period of rebuilding, and not until 1143 was the new High Altar finally consecrated, but by this time Hildegard had her own establishment. The watershed of her life was perhaps about her fortieth birthday. Jutta died and she became abbess of the community of young women that had grown up in the enclosure. The visions took on an urgency that demanded a wider audience, and she found that she needed her own establishment, she needed to found her own garden, her city of God. Perhaps the long years of rebuilding the Disibodenberg had given her a taste for planning and constructing. Certainly she found that she could not work as a dependent of Abbot Kuno and his community. The Rupertsberg She went to the Rupertsberg, a scrubby hill overlooking Bingen, where the Nahe meets the Rhine in a great wide curve, just above the entrance to the gorges. It is roughly halfway between the great archbishoprics of Trier and Mainz, and halfway between the cities of Cologne and Mainz, firmly on the greatest river highway between northern and southern Europe. Indeed, there was a still-robust Roman army bridge over the Nahe at Bingen, making it an important stop on the east-west routes through the Empire as well. The establishment of the cloister was not easy. There had been no appreciable previous cultivation on the hill, and the nuns had to build and farm from scratch. Some of the more pampered young ladies complained bitterly and left for more comfortable convents. There were political problems too. Abbot Kuno and the monks of the Disibodenberg resented losing not only a dynamic and charismatic abbess, but the entire flock of well-connected and wealthy young women whose dowries, given to the church on their entering it, would now transfer automatically to the new establishment. Hildegard fought, with the help of her family and of various noble relations of her nuns, and eventually won complete independence from her former home, becoming answerable directly to Mainz. She continued throughout her life to maintain as much political independence as possible, using her aristocratic connections to influence church authorities, and vice versa. As her fame spread, she used the power this gave her to say some extraordinarily direct things. She became known as the prophetissa teutonica, ‘prophetess’ here being used in a biblical sense, i.e. a person who reveals what exists and is hidden from ordinary mortals, rather than specifically foreseeing the future - though she did predict various events, in an apocalyptic kind of way, and later writers, particularly in the seventeenth century, interpreted these as foretelling certain aspects of the Reformation. A prophet is also the voice of a community’s conscience, and she was certainly concerned with reformation in her own time: many of her letters to abbots and abbesses contain severe admonishments to moderate their lifestyles. She was not above castigating an Emperor - a letter to Frederick Barbarossa tells him quite brusquely not to be so childish, to stop appointing antiPopes and accept the authority of Holy Mother Church in Rome. In addition to writing and composing, Hildegard travelled extensively through the Rhine and Mosel valleys, giving counsel publicly and privately. Only very occasionally was she thwarted, notably towards the very end of her life: she had allowed a man to be buried whom she considered to be absolved, but whom the Mainz authorities had excommunicated. As a result the entire convent was also excommunicated, not allowed to receive the sacraments and not allowed to sing the offices. This drove her to write one of her most passionate letters in which she declares that music is at the heart of the relationship between God and Mankind. Hildegard possessed a most extraordinary energy. She was often confined to bed with bouts of ill-health, frequently associated with the great visions and the rigors of trying to express their message. However, she was granted an astonishing strength, and during a long lifetime - she lived until the very ripe old age of 82 - produced three great books of visionary theology, several collections of writings on natural history and medicine, 77 songs for liturgical use, and the Ordo Virtutum. Ordo Virtutum This work is extraordinary on several counts - it is not only one of the earliest medieval morality plays, but the earliest musical play extant, since everything is sung, except for the Devil, who speaks, making a mere noise (strepitus). The vision on which it was based forms the last part of the Scivias (see below), where Hildegard describes the City of God, the New Jerusalem - not quite perfect, because built by mankind’s endeavours, but filled with the light of the Spirit, and populated by patriarchs and prophets, holy men and women, angels and saints, and those who guide them, the virtues. The word meant ‘strength’ rather than the more passive kind of goodness we now tend to associate with the word, and these Virtues personify the moral strengths that men need and will be given to reach the City of God. Hildegard saw them in great detail, and it is very likely that costumes based on the vision were made and worn for performances of the Ordo on the Rupertsberg. A neighbouring abbess, Tengswich, accused Hildegard of letting her nuns wear tiaras and fine robes on feast days, to which Hildegard replied that virgins were allowed to adorn themselves for Christ. Her last secretary, Guibert of Gembloux, also wrote to her, rather more sympathetically, asking about the tiaras. She replies ‘why should all the ranks of the Church have glorious emblems, and virginity have none but a black veil?’ and describes a vision where she sees virginity clothed in white, and wearing crowns signifying the Trinity. The Scivias - Know the ways of the Lord - is the first of the great visionary books, and deals with the creation of the world, the nature of the Trinity, and the building of the City of God - man’s final goal. It was followed by the Liber vitae meritorum [Book of the merits of life], which deals more precisely with the relationship of God and Man, and finally by the Liber divinorum operum [The Book of Divine Works], which addresses the relationship between the whole creation and God. The books are divided into sections, each dealing with a vision or a detail of a larger vision, which is described in some detail, together with the explanations spoken by the voice of the Living Light, and followed by Hildegard’s own exegesis. In many cases there is also an actual painting of the vision, and most writers agree that these are largely contemporary with the writing, and if not directly from Hildegard’s pen, then drawn under her direct supervision. The link with migraine Since the medical historian Charles Singer first wrote about this in 1917, others have also seen links between aspects of Hildegard’s visions and the visual disturbances associated with classical migraine aura. It is perfectly true that elements such as the walls of light, the falling stars and the black clouds remind one of the fortification spectra, phosphenes and negative scotomata of the migraine aura. It is also interesting that Hildegard always maintained that she never went into a trance or ecstasy to see these things, but saw them waking. She doesn’t seem to have suffered unduly from migraine headache, though she suffered physically before and after the visions. Oliver Sacks, in his excellent book Migraine, shows that both causes and after effects are enormously varied, and that the nature of any one person’s experience is deeply bound up with that person considered as a whole. The complexity and integrity of Hildegard’s seeing cannot be reduced to an electric malfunction in the brain, even if that is where it physically started. One detail, however, I find particularly significant. She describes the illnesses preceding the visions of the Liber vitae meritorum (1158-63) thus: aerial torments dried up her veins and marrow, a fire convulsed her womb. A good angel invited her to heaven, but the angelic throng said not yet. This angel calls her not columba, dove (as one might expect an angel to name a virgin) but aquila, eagle - the strong, noble bird that soars nearer heaven than any other creature, and that possesses the courage to look straight into the sun. For me that could suggest the dazzling lights of a scotomata attack, and the strength of mind to look beyond the physical manifestation to its spiritual cause. Hildegard’s influence today When the Thirty Years War devastated the Rheinland in the seventeenth century, the old cloister on the Rupertsberg was partly destroyed, to be completely demolished when the railway was built down the Rhein valley in the nineteenth century. However, Hildegard had established a daughter foundation, at Eibingen above Rüdesheim on the opposite bank of the Rhein. This survived until the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was dissolved by the secular napoleonic authorities, and the buildings, except for the church, fell into disuse. But through the century, interest in Hildegard and her foundation gradually increased, and at the turn of the century a new Benedictine convent was built on the hill just above the village of Eibingen. This Abbey of St Hildegard flourishes to the present day, a severely beautiful and impressive building in the Byzantine style, looking over vineyards and the wide, still unbridged, river to Bingen and the vanished site of the Rupertsberg. In recent years, Hildegard’s fame has spread swiftly, particularly in German speaking areas. Even her medical ideas are enjoying a new lease of life (recently published: Hildegard’s Sweet Chestnut Recipe Book, Cures for Women’s Ailments, Keeping Body and Soul Healthy), and indeed, although we may not agree with her science, there is nothing wrong with her basic premise that a natural equilibrium exists, slightly different for each individual creature, but that balances body, mind and soul. She has inevitably also attracted theologians interested in discussing the femininity of the Divine, and equally inevitably there has been some distortion of her ideas by people eager to show how modern her thinking is. But she also belongs, as Barbara Newman’s book Sister of Wisdom shows, to a long tradition, reaching back into both the Greek and Judaic past, of understanding divine Love and Wisdom - Caritas and Sapientia or Sophia - as the feminine nature of God, as a maternal, nurturing, fertile force. Her concept of the Virgin Mary is bound up with this, and is complex, radical and dynamic. For her, the Virgin reverses Eve’s sin, by bearing the son of God, the Mediator. The wordplay is a familiar one - the angel’s Ave (Maria) reversing Eva’s name - but Hildegard takes it to poetic heights hitherto unscaled. In Hildegard’s theory of creation, Mary is Salvatrix and redeems matter, and women are closer to the image of God than men. Whatever the origins of Hildegard’s visions (and if the Holy Spirit can fertilise a virgin’s womb then why shouldn’t it trigger a synapse in another’s brain?), the corpus of her work shows an astonishing mind, curious about everything in the creation and beyond, concerned to see and show the links between all things. The vision creates an overwhelming pressure to transmit the experience to others - and not only the vision, but the words spoken in the vision, and the song of the angels. Hildegard is working on every level, expressing herself through her intellect, through the visual arts, through poetry, and through her music. Judging from the way in which she writes about music right at the end of her life, of all of these it is music that runs the most deeply and powerfully in her, the dynamic expression of the love of God and of his promise to bring mankind back to Him, the expression in the body of the green growing grace of viriditas. |